Prying the Elizabethan culture of courtship and sprezzatura

from The Tempest was not the labor of

layered symbolism I thought it to be; sprezzatura lurks just beneath the

surface. Of course it would. In a play where nearly every character lays claim

to nobility of some sort – even Caliban, original sovereign of the isle –

everything they do and say is a reflection of courtly life.

Instance the first: Ferdinand’s obsession with Miranda, and

their relationship, of sorts. Their first impressions of each other are, “Oh!

How beautiful” – a reflection of Castiglione’s argument of beauty being

inherent of goodness. Declared Miranda, “There’s nothing ill can swell in such

a temple” (1.2 Line 457). It's the classic "you look awesome; therefore you can do no wrong" attitude of the day.

More interesting, however, is the way the different characters

approach leadership and servitude.

In Act 2 Scene 1, lines 148-165, Gonzalo proposes an idyllic

government reminiscent of the Garden of Eden. Not a soul would toil nor engage

in commerce, the land would produce – on its own – everything necessary for

life, and the people would live in a state of perfect peace. His idea is shot

down rather quickly, but it demonstrates, perhaps, two ideals. One: that

nobility is marked by not needing to work. In Gonzalo’s island, everyone would

be idle and happy. Two: such a state of existence would be the direct result of

Gonzalo’s leadership. Somehow, by doing nothing, his subjects wouldn’t have to

do anything, either.

"Rich and privileged as the nobility are," wrote Ian Mortimer, "it is the gentry to own and run England. They are the five hundred or so knights with country estates, and approximately fifteen thousand other gentlemen with an income from land sufficient to guarantee they do not have to work for a living."

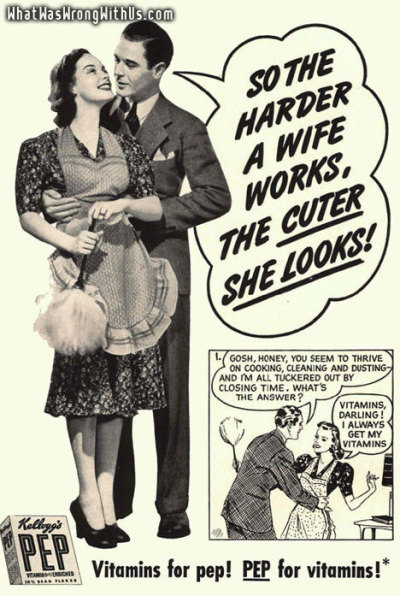

This is reflected in Miranda’s attitude toward Ferdinand

performing regular household chores. Her implorations for him to rest become

somewhat of an argument: each is convinced that the other is too dignified for

menial work, and each is insistent on doing it (the chore) to alieve the other’s

burden. Said Ferdinand, “I had rather crack my sinews, break my back / Than you

should such dishonor undergo / While I sit lazy by” (3.1 25-27). To which

Miranda replied, “It would become me / As well as it does you” (3.1 28-29). (Somewhat

unrelated to Sprezzatura, this latter declaration was fascinating to me in that

Miranda asserts herself as Ferdinand’s equal – in dignity, and in her capacity

to perform physical labor.)

|

| Original Image |

Ferdinand’s insistence – indeed, obsession – with serving Miranda

is reminiscent, in turn, of Elizabeth’s position as the unattainable virgin.

Her beauty inspires those around her to serve and protect her, quite

selflessly. As noted by Ferdinand, “The mistress which I serve quickens what’s

dead, / And makes my labours pleasures” (3.1 6-7). As contrasted by Caliban’s

servitude, inspired in turns by fear of punishment and desire for liquor.

Ferdinand seems to represent what happy servitude looks like and ought to be;

Caliban, on the other hand, is nothing noble and seems to show how not to go

about it.

Works Cited

Shakespeare, William. The

Tempest. Ed. Virginia Mason Vaughan, Alden T. Vaughan. Bloomsbury

Arden Shakespeare: London (2014). Print.

Mortimer, Ian. "The Gentry." The Time Traveler's Guide to Elizabethan England. Penguin (2013). Print.

Why do you think that there seems to be no sprezzatura with Prospero? Is it because he's old or because he is the father figure? Maybe it just wasn't a focus of Shakespeare for that character, but I really love the points that you bring up about Ferdinand and Miranda's relationship being a sort of mini-courtly-romance.

ReplyDeleteOh, there was lots of sprezzatura with Prospero. There's a moment that really caught my eye when Miranda, countering her father's harsh treatment of Ferdinand, says "My father's of a better nature, sir / Than he appears by speech" (1.2). It's completely antithetical to the Sprezzatura belief that the inward character of a man can be measured by his outward appearance, suggesting that Prospero is meant to be a difficult character that calls traditional values into question.

ReplyDeleteWell, I meant why didn't he portray the same kind of courtesy, which as you point out, he doesn't. So he's the opposite of sprezzatura in a way.

Delete